Book Review – The Fourth Turning

I.

America is in a state of decline. Our government is inept — ambitious public projects like the Apollo program and the construction of the Interstate Highway System are little more than a fading memory of a once-competent system. The culture wars have fragmented us. We live in different realities depending on partisan affiliation, leading to less understanding and tolerance of our neighbors. The stock market (at least until recently) has been roaring, but wages are stagnant and wealth is increasingly concentrated in the hands of a lucky few.

What is the solution to these problems? Many would take a rationalist approach:

- Challenge the premise of these very questions. Are these problems really worse than they were in the past? Or is this just lazy storytelling without any data to back it up?

- Launch and fund experiments that attempt to solve these pressing issues. (Grants programs, blog prizes, etc.) As a second order effect, gather data to become better at addressing other problems facing humanity.

- Preach a gospel of tolerance. We can seek to understand others’ perspectives, as well their biases and incentives (as well as our own!). From a new place of shared understanding, address specific difficulties with targeted interventions.

A symptom of American decline

William Strauss and Neil Howe deal with these problems in a different way. The one-word summary of The Fourth Turning is “fatalism”. Our society is currently undergoing a natural “unraveling” that will cumulate in a World War II-scale conflict. Now is the time to prepare for that certainty.

II.

If you want a data-driven argument backed by a great degree of research, look elsewhere. This is a book full of bold, plausible but unsubstantiated claims, and lots of dunking on Boomers (before it was cool).1

Strauss and Howe argue that time is a flat circle:

Over the past five centuries, Anglo-American society has entered a new era—a new turning—every two decades or so. At the start of each turning, people change how they feel about themselves, the culture, the nation, and the future. Turnings come in cycles of four. Each cycle spans the length of a long human life, roughly eighty to one hundred years, a unit of time the ancients called the saeculum. Together, the four turnings of the saeculum comprise history’s seasonal rhythm of growth, maturation, entropy, and destruction:

- The First Turning is a High, an upbeat era of strengthening institutions and weakening individualism, when a new civic order implants and the old values regime decays.

- The Second Turning is an Awakening, a passionate era of spiritual upheaval, when the civic order comes under attack from a new values regime.

- The Third Turning is an Unraveling, a downcast era of strengthening individualism and weakening institutions, when the old civic order decays and the new values regime implants.

- The Fourth Turning is a Crisis, a decisive era of secular upheaval, when the values regime propels the replacement of the old civic order with a new one.

People both shape and are shaped by history. So these turnings are driven by generational archetypes, as follows:

- A Prophet generation grows up as increasingly indulged post-Crisis children, comes of age as the narcissistic young crusaders of an Awakening, cultivates principle as moralistic mid lifers, and emerges as wise elders guiding the next Crisis.

- A Nomad generation grows up as underprotected children during an Awakening, comes of age as the alienated young adults of a post-Awakening world, mellows into pragmatic midlife leaders during a Crisis, and ages into tough post-Crisis elders.

- A Hero generation grows up as increasingly protected post-Awakening children, comes of age as the heroic young teamworkers of a Crisis, demonstrates hubris as energetic midlifers, and emerges as powerful elders attacked by the next Awakening.

- An Artist generation grows up as overprotected children during a Crisis, comes of age as the sensitive young adults of a post-Crisis world, breaks free as indecisive midlife leaders during an Awakening, and ages into empathetic post-Awakening elders.

The book gives examples of various Prophets, Nomads, Heroes, and Artists throughout history. Near as I can tell, Strauss and Howe take the most known historical figures from each generation, then call them out as exemplary of whichever generation they happened to fall into.

George Washington and Abraham Lincoln have to be heroes, right? Nope! George Washington was a Nomad (the best-known Hero of that time would be Thomas Jefferson) and Abraham Lincoln was a Prophet. But perhaps I’m being too harsh. These archetypes are meant to be a metonym for the generation as a whole, not indicative of individuals who are a part of the generation.

Strauss and Howe then give a vague appeal to “wisdom of the ancients” and cherry-pick examples from the past to demonstrate that a cyclical and generational interpretation of history is correct. Their narratives, while falling victim to selection bias, are compelling.

They emphasize Hero Myths: stories of a young hero and elder prophet. This generational combination shepherds society through a crisis. Think Luke Skywalker and Obi-Wan Kenobi in Star Wars or Frodo and Gandalf in The Lord of the Rings.

Myths involving young hero-kings and old prophets are universal in part because people are comforted to hear tales of the valor of youth tempered by the wisdom of age. Yet people of all eras know that such a mythlike symbiosis between young and old occurs only on occasion. In America, certainly, it has not been present for decades. The last time heroic youth and wise elders had this kind of constructive relationship was using World War II. The reason these young Hero Myths are so embedded in our civilization is because they explain events when the secular world (the domain of kings) is being redefined beyond prior recognition—in other words, in Crisis eras.

Prophet myths are the mirror image of Hero myths.

While the Hero Myth ends in the palatial city, the Prophet Myth starts there.

Consider Siddhartha escaping the pleasures of the material world and seeking spiritual redemption, or Jesus overturning the money changers’ tables in the Temple courtyard.

Perhaps the most convincing example of a generational myth The Fourth Turning highlights is the biblical story of Exodus. Moses and his peers were Prophets, who defied the worldliness of Pharaoh in Egypt to turn towards God during an Awakening. Their children (Nomads) were alienated young adults who worshipped the Golden Calf. They defied their elders and were lost in both time and space during an Unraveling, wandering in the desert between the worlds of Egypt and the Promised Land. Then came the Heroes: Joshua’s generation of soldiers who led the Israelites through the battles of a Crisis and into the Promised Land. This generation presided over a new High and then gave way to the Judges, an Artist generation that ruled at time of “political fragmentation, cultural sophistication, and anxiety about the future.”

III.

Around this part of the book, I started to feel like I was part of a cult – one whose prophecy had failed. This book was written in 1997, midway through Strauss and Howe’s Third Turning. So I have the benefit of 25 years of history to look back on.

But back in the 1990s, Strauss and Howe had utter certainty in their theory, claiming:

In linear time, there would be no turnings, just segments along one directional path of progress…The 2020s would be a mere extrapolation of the 1990s, with more capable channels and Web pages and senior benefits and corporate free agents—plus more handgun murders, media violence, cultural splintering, political cynicism, youth alienation, partisan meanness, and distance between rich and poor.

Isn’t this exactly what happened? This appears to invalidate the book’s entire premise of a 80-100 year historical cycle. Do not pass go, do not collect $200.

On the other hand, some of the trends we saw in the 1990s have in fact reversed. Liberalism certainly appears to be declining. America is becoming more isolationist. Our political parties have completely flipped – the Trumpian Republicans of today would be alien to the Republicans of the 1990s.

Perhaps our society is unraveling.

IV.

But I digress. Having established their theory of historical and generational cycles, Strauss and Howe now dive deep into the past 100 years.

These 150 or so pages read like most business books: there is the kernel of an interesting idea and enough content for a 15-minute TED Talk, with a whole lot of filler to meet a minimum word count. Most readers will be familiar with the generations presented:

- G.I. Generation (more commonly known as the Greatest Generation)

- Silent

- Baby Boomers

- Gen X

- Millennials2

- New Silent (Gen Z)3

Strauss and Howe examine how these different generations have influenced and moved through the past three turnings in American history.

The First Turning was the post-World War II High of 1946-1964.

This was the most boring chapter of the book, with the exception of this notable zinger:

“Surrounded by such open-handed generosity, child Boomers developed what Daniel Yankelovich termed the “psychology of entitlement.” Landon Jones recalls how “what other generations have thought privileges, Boomers thought were rights.”

The Second Turning was the Consciousness Revolution of 1964-1984.

Here we have more quips, expanding the attack surface to Gen X in addition to Boomers:

Back in the High, being a good adult had meant staying married and providing children with a wholesome culture and supportive community. Now it meant festooning the child’s world with self-esteem smiley buttons while the fundamentals (and media image) of a child’s life grew more troubled by the year.

This Awakening period produced more examples of fatalism from Strauss and Howe.

Perhaps Vietnam’s civil war would have been a fixable foreign problem back in the High, but American intervention was doomed to failure in the Awakening.

Plausible theory. But this is but one factor to be considered. Solely focusing on the Awakening denies the agency of the North Vietnamese, the influence of the Soviets, and essentially anything other than the culture of the US at the time.

This section of the book also highlighted how we are still seeing the effects of 1970s policy today.

By the late 1970s, transfer payments from younger generations to G.I.s towered (by a ten-to-one ratio) over what remained of Great Society poverty programs.

There were also several quotes that made me think that Millennials and Boomers are more similar than they first appear, defying the ebb-and-flow generational theory presented in the book.

Where Silent beatniks had expressed angst in poetry, earnestly seeking audiences, Boomer hippies megaphoned their “nonnegotiable demands” without much caring who listened. In the new youth culture, purity of moral position counted most, and “verbal terrorism” silenced those who dared to dissent from dissent.

You could print that sentence verbatim in a conservative publication today! Also:

Rather than ask students to evaluate a book’s universal quality or message, teachers began probing students about how a reading assignment made them feel. Grammar was downplayed, phonics frowned on, and arithmetic decimals replaced by the relativistic parameters of New Math.

Strauss and Howe also present some interesting facts I wasn’t aware of:

The abortion rate skyrocketed; by the late 1970s, would-be mothers aborted one fetus in three.

At the same time,

The ascendant Zero Population Growth movement declared each extra child to be “pollution,” a burden on scarce resources.

This seems similar to what I thought was a more recent phenomenon of people giving up on having kids due to climate change.

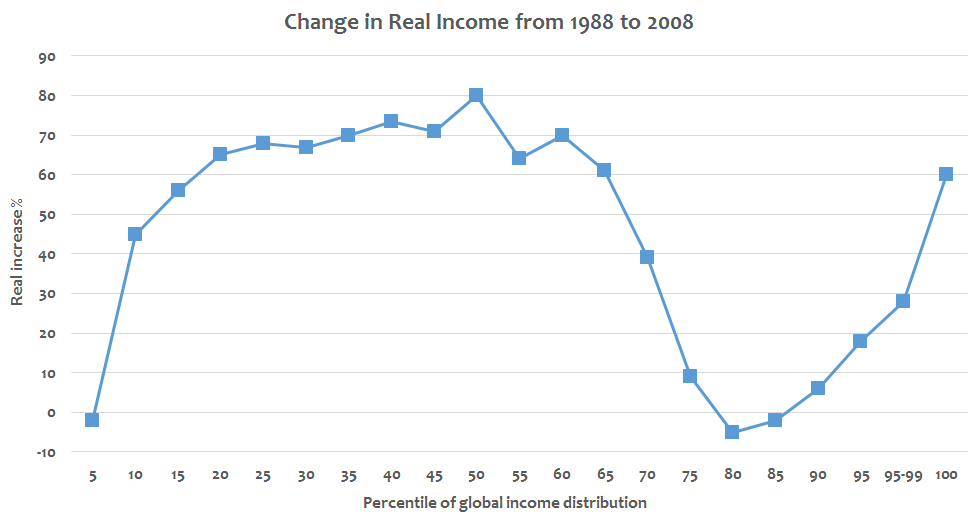

Overall, Strauss and Howe raise some interesting points about the period. But their theories are incredibly US-centric and solely sociological, as opposed to economic. They note that real wages have been declining since 1973, but don’t address forces of globalization or anything that could account for it outside of their theory. Quite frankly, I think globalization hollowing out the US middle class presents a more compelling explanation for the societal forces at play than a generational theory of history.

The Elephant Curve: The best explanation of US economics and politics over the past 50 years

The Third Turning was the Culture Wars of 1984-2005.

Here, the book starts to warm up. The book was written midway through this Unraveling period. So this section both summarized what was going on in the early 1990s, as well as offered predictions for the coming decades.

Strauss and Howe’s definition of “Culture Wars” seems quaint, like a minor leagues version of the culture wars in American society today.

By the early 1990s, America’s niche group conflict came to be known as the Culture Wars, defined by Irving Kristol as a “profound division over what kind of country we are, what kind of people we are, and what we mean by ‘The American Way of Life.’” Three basic battlegrounds emerged: multiculturalists against traditionalists (the Sheldon Hackneys versus the William Bennetts), media secularists against evangelicals (the Murphy Browns versus the Dan Quayles), and public planners against libertarians (the Robert Reichs versus the Charles Murrays). The Culture Wars had as many combatants as America had niches, from the Nation of Islam to the Internet. As each group exalted its own authenticity, it defined its adversary’s values as indecent, stupid, obscene, or (a suddenly popular word) evil.

Finally, Strauss and Howe address some basic economics that could be contributing to societal unrest.

In 1955, most thirty-five-year-olds typically lived in bigger houses and drove better cars than their sixty-year-old parents. Now the opposite is the case. As entry-level pay and benefits have shrunk for young workers, top-level pay has skyrocketed for their aging bosses: Where a G.I. CEO earned 41 times the pay of an average worker, a Silent CEO earns 225 times as much.

The authors also display mild misogyny, but draw mostly correct conclusions about a Red Queen’s race in which two-income households are barely better-off than one-income households a generation ago.

Boomer men have largely accepted their female peers’ incursions. Without a second income, most of their households would fall below the living standards of the Silent at like age.

There are some predictive gems. For example,

In affluent suburbs, Boomer homes will buzz with offices, day care co-ops, food delivery, phone shopping, and other infrastructure around which will grow a new civic life, at times behind scurry gates. Those who love far from their parents and childhood homes will struggle toward their own definition of real community.

Accurate! The problem is that only about 25% of their forecasts are as on-target as this one. The others are just as bold, but entirely incorrect. Here’s one that is risible:

Colleges will be pressured into holding the line on tuitions and student indebtedness, faculties into putting teaching ahead of research, employers into creating apprenticeships, older workers into making room for the young.

As the book moves closer to the present, Strauss and Howe earn points for pointing out that the Greatest Generation kicked off a wealth transfer to elders that never ended. But again, their arguments could be strengthened if they factored in basic economics. In particular, the post-World War II era was a striking historical anomaly: a lack of global manufacturing competition allowed the US to have a robust blue-collar economy and high living standards. One could argue that we are now simply reverting to the mean.

Take the example of where people want to live. In a simplified model: Cities were crime-ridden in the 1970s and those with wealth lived in the suburbs. Then, yuppies moved to the cities, making them vibrant cultural centers and driving up rents. The stereotypical Millennial valued experiences over things, living in a cramped apartment but traveling to Europe twice a year. When COVID hit, this trend reversed – people moved back to the suburbs, valuing space to be outside and work from home over an urban lifestyle.

You could explain all of that with a sweeping theory of generational cycles. Or through an introductory class in microeconomics.

Generational cycles, or simply supply and demand? Image via CFI

Strauss and Howe also have a strong bias towards conservatism and traditional family values. They go on and on about no-fault divorce laws being overturned. This is something that, as a Millennial, I didn’t even realize was or could be a hot-button issue.

After a while, this section just started to read as [Silent/Boomers/Gen X] will [insert semi-vague astrological prediction here] followed by [snappy out-of-date cultural reference].

Gradually, the old wry detachment will give way to a jarring new focus. Boomers will at long last be ready to accept full responsibility for their own old age—and for the hard choices facing their nation. Increasingly, graying Boomers will “muster the will to remake ourselves into altruists and ascetics,” as Rolling Stone urged in 1990. “But let’s not fake it,” the magazine warned, the yuppie persona still in its rearview mirror. Or at the very least, advises Hillary Clinton, “fake it until you make it.” By the Oh-Ohs, this generation will be of no mind to fake anything. “There is no way to avoid the coming confrontation,” the Catholic Eye declared in 1992. “Fasten your seat belts—it’s going to be a rough ride.”

V.

Winter is coming.4

Strauss and Howe boldly claim:

Sometime before the year 2025, America will pass through a great gate in history, commensurate with the American Revolution, Civil War, and twin emergencies of the Great Depression and World War II.

We’re running up against their deadline, so I find myself hunting for events that fit their framework:

- A Crisis era begins with a catalyst—a startling event (or sequence of events) that produces a sudden shift in mood.

- Once catalyzed, a society achieves a regeneracy—a new counter entropy that reunifies and reenergizes civic life.

- The regenerated society propels towards a climax—a crucial moment that confirms the death of the old order and birth of the new.

- The climax culminates in a resolution—a triumphant or tragic conclusion that separates the winners from losers, resolves the big public questions, and establishes the new order.

We will fall on hard times, and either emerge stronger as a society or crumble. Strauss and Howe claim that the product of societal disquietude will be compulsory military service and a rigid society – perhaps even a new American form of fascism.

The prospect for great civic achievement—or disintegration—will be high. New secessionist movements could spring from nowhere and achieve their ends with surprising speed. Even if the nation stays together, its geography could be fundamentally changed, its party structure altered, its Constitution and Bill of Rights amended beyond recognition. History offers even more sobering warnings: Armed confrontation usually occurs around the climax of Crisis. If there is confrontation, it is likely to lead to war. This could be any kind of war—class war, sectional war, war against global anarchists or terrorists, or superpower war. If there is war, it is likely to culminate in total war, fought until the losing side has been rendered nil—its will broken, territory taken, and leaders captured. And if there is total war, it is likely that the most destructive weapons available will be deployed.

They also (accurately) predict a decline in social trust.

The new mood and its jarring new problems will provide a natural end point for the Unraveling-era decline in civic confidence. In the pre-Crisis years, fears about the flimsiness of the social contract will have been subliminal but rising. As the Crisis catalyzes, these fears will rush to the surface, jagged and exposed. Distrustful of some things, individuals will feel that their survival requires them to distrust more things. This behavior could cascade into a sudden downward spiral, an implosion of societal trust.

Maybe we’re in the midst of a Crisis already! Since the book has been written, we’ve gone through: 9/11, wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, a financial crisis, and a global pandemic. But do any of these qualify as extreme enough to be a Crisis, on par with World War II or the Civil War? Consider the scenarios the authors lay out for the Fourth Turning:

- Beset by a fiscal crisis, a state lays claim to its residents’ federal tax monies. Declaring this an act of secession, the president obtains a federal injunction. The governor refuses to back down. Federal marshals enforce the court order. Similar tax rebellions spring up in other states. Treasury bill auctions are suspended. Militia violence breaks out. Cyberterrorists destroy IRS databases. U.S. special forces are put on alert. Demands issue for a new Constitutional Convention.

- A global terrorist group blows up an aircraft and announces it possesses portable nuclear weapons. The United States and its allies launch a preemptive strike. The terrorists threaten to retaliate against an American city. Congress declares war and authorizes unlimited house-to-house searches. Opponents charge that the president concocted the emergency for political purposes. A nationwide strike is declared. Foreign capital flees the U.S.

- An impasse over the federal budget reaches a stalemate. The president and Congress both refuse to back down, triggering a near-total government shutdown. The president declares emergency powers. Congress rescinds his authority. Dollar and bond prices plummet. The president threatens to stop Social Security checks. Congress refuses to raise the debt ceiling. Default looms. Wall Street panics.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announce the spread of a new communicable virus. The disease reaches densely populated areas, killing some. Congress enacts mandatory quarantine measures. The president orders the National Guard to throw prophylactic cordons around unsafe neighborhoods. Mayors resist. Urban gangs battle suburban militias. Calls mount for the president to declare martial law.

- Growing anarchy throughout the former Soviet republics prompts Russia to conduct training exercises around its borders. Lithuania erupts in civil war. Negotiations break down. U.S. diplomats are captured and publicly taunted. The president airlifts troops to rescue them and orders ships into the Black Sea. Iran declares its alliance with Russia. Gold and oil prices soar. Congress debates restoring the draft.

The second-to-last option sounds like COVID and the protests/riots that ensued in the summer of 2020. The last bullet point is eerily similar to the current war in Ukraine. If Russia’s invasion of Ukraine kicks off World War III, I take back my criticisms of Strauss and Howe and am completely on board with their predictions.

But overall I’m still skeptical – these are bold forecasts that I suspect overfit to the training data, much more hedgehog than fox. In perhaps the biggest leap of faith the authors make, they claim that baseball players offer a lesson in seasonality and help to predict the Fourth Turning.

The national pastime—baseball—offers a similar lesson in seasonality. Each of the last four turnings produced an extraordinary player whose manner was much admired but, being preseasonal, did not yet define the rewarded norm. Lou Gehrig illustrated this before the last Crisis, Joe DiMaggio before the High, Jackie Robinson before the Awakening, Reggie Jackson before the Unraveling, and Cal Ripken now. Ripken’s Gehrig-like virtue is distinctly Fourth Turning. Yet while it is admired by many people, it is not the kind of in-your-face, high-stepping, free-agent behavior that still sells most Unraveling-era tickets.

I mean, come on.

VI.

What should we do to prepare for this looming Crisis?

Essentially, Strauss and Howe give some lightweight prepper advice here. This section of the book is remarkably simple and practical.

You can’t depend on the government to save you – you’re on your own. Save money, hoard resources, foster a mindset of self-reliance and frugality. Learn skills that will be useful in a Crisis era, like farming, hunting, and first aid. Then be generous in sharing those skills with your community. With a good reputation and a desirable, well-known skillset, you’ll be positioned to band together with a small tribe to ride out the Crisis.

This is good advice, even if a Crisis does not come to pass. In an increasingly specialized world, many of us lack basic survival skills. Promoting a culture of self-reliance is probably a good thing.

Beyond that, there’s not much to be done. Zooming out to the national level, Strauss and Howe show prescience here about how political parties have shifted over the past 20 years:

Neither of the two major political parties has been adept at seasonalist thinking. The Republicans were worse at figuring out what the early Awakening required, the Democrats worse at the early Unraveling. With the Fourth Turning roughly a decade away, each party now has it half right: Democrats have seized the saeculum’s autumnal instinct to harvest, Republicans the instinct to prune and scatter. Each party is usefully pressing for some preseasonal policies: Democrats wish to close the gap between rich and poor, reverse the decline of the middle class, and expand children’s programs—while Republicans want to de-fund time-encrusted bureaucracies, restore an ethic of personal responsibility, and promote traditional virtues.

Yet both parties are also harmfully postseasonal. In their quest for an ever bigger harvest, Democrats want to remove sacrifice ever further from the public lexicon. They seek entitlements for every victim, including the entire middle class, without caring whether all this guaranteed consumption is sustainable. If Democrats get their way, they would impose huge debts and future taxes on Millennial children. In their quest for ever more individualism, Republicans want to make public authority ever more dysfunctional. They seek to starve all government of revenue and are willing to shut down whole federal agencies to make their point. If Republicans get their way, they would prevent Millennials from forging a positive bond with government and limit the public resources directed toward the care and schooling of the neediest children.

Despite the doom and gloom, the book ends on an uplifting note. Yes, the Fourth Turning could usher in a Mad Max age. Or, we could emerge as a stronger, more robust society.

The Fourth Turning could spare modernity but mark the end of our nation. It could close the book on the political constitution, popular culture, and moral standing that the word America has come to signify. This nation has endured for three saecula; Rome lasted twelve, Etruria ten, the Soviet Union (perhaps) only one. Fourth Turnings are critical thresholds for national survival. Each of the last three American Crises produced moments of extreme danger: In the Revolution, the very birth of the republic hung by a thread in more than one battle. In the Civil War, the union barely survived a four-year slaughter that in its own time was regarded as the most lethal war in history. In World War II, the nation destroyed an enemy of democracy that for a time was winning; had the enemy won, America might have itself been destroyed. In all likelihood, the next Crisis will present the nation with a threat and a consequence on a similar scale.

Or the Fourth Turning could simply mark the end of the Millennial Saeculum. Mankind, modernity, and America would all persevere. Afterward, there would be a new mood, a new High, and a new saeculum. America would be reborn. But, reborn, it would not be the same.

Interestingly, this book is a favorite of Steve Bannon’s. Was the Trump presidency a symptom of the Fourth Turning, or something that aided in bringing it about? The authors of this book would argue that it is both.

Overall, The Fourth Turning is a thought-provoking read. It challenges our linear view of history and reminds us that there is no law of nature stating that society will march forward unabated toward greater wealth and technological progress. In fact, for most of human history this was not the case.

But the book was also much longer than it needed to be. You’re better off reading a summary, studying some economics, and reflecting on the ending epigraph, which is much more Lindy:

To every thing there is a season,

and a time to every purpose under heaven:

a time to be born, and a time to die;

a time to plant, and a time to pluck up that which is planted;

a time to kill, and a time to heal;

a time to break down, and a time to build up;

a time to weep, and a time to laugh;

a time to mourn, and a time to dance;

a time to cast away stones, and a time to gather stones together;

a time to embrace, and a time to refrain from embracing;

a time to get, and a time to lose;

a time to keep, and a time to cast away;

a time to rend, and a time to sew;

a time to keep silent, and a time to speak;

a time to love, and a time to hate;

a time of war, and a time of peace.

—Ecclesiastes 3.1-8

Notes:

-

My personal favorite: Boomers are “a destructive generation whose work is not over yet.” ↩

-

A term coined by Strauss and Howe! ↩

-

This generation is only briefly touched upon, since they would not yet have been born when the book was published. ↩

-

I wonder if William Strauss and Neil Howe were George R.R. Martin fans, as they use this exact phrase in the book. ↩