January 4, 2021

Applied Divinity Studies asks: “Why don’t people quit their jobs at large tech companies?”

We can explore this phenomenon through a machine learning analogy. I propose that human beings are awful at optimizing explore - exploit algorithms.

Careers as Gradient Descent

A useful metaphor for our careers is a hill climbing algorithm. Imagine that you are dropped at a random point in a hilly area. Your goal is to get to the top of the highest hill. The problem is, you can only see a few feet in front of you.

If you only move uphill, you risk getting stuck at a local maximum. You’ve gotten to the top of a hill, but there’s no way to know if it’s the highest one in the area. So there needs to be some element of randomness your steps – you need to take downhill steps in order to explore different hills in the terrain.

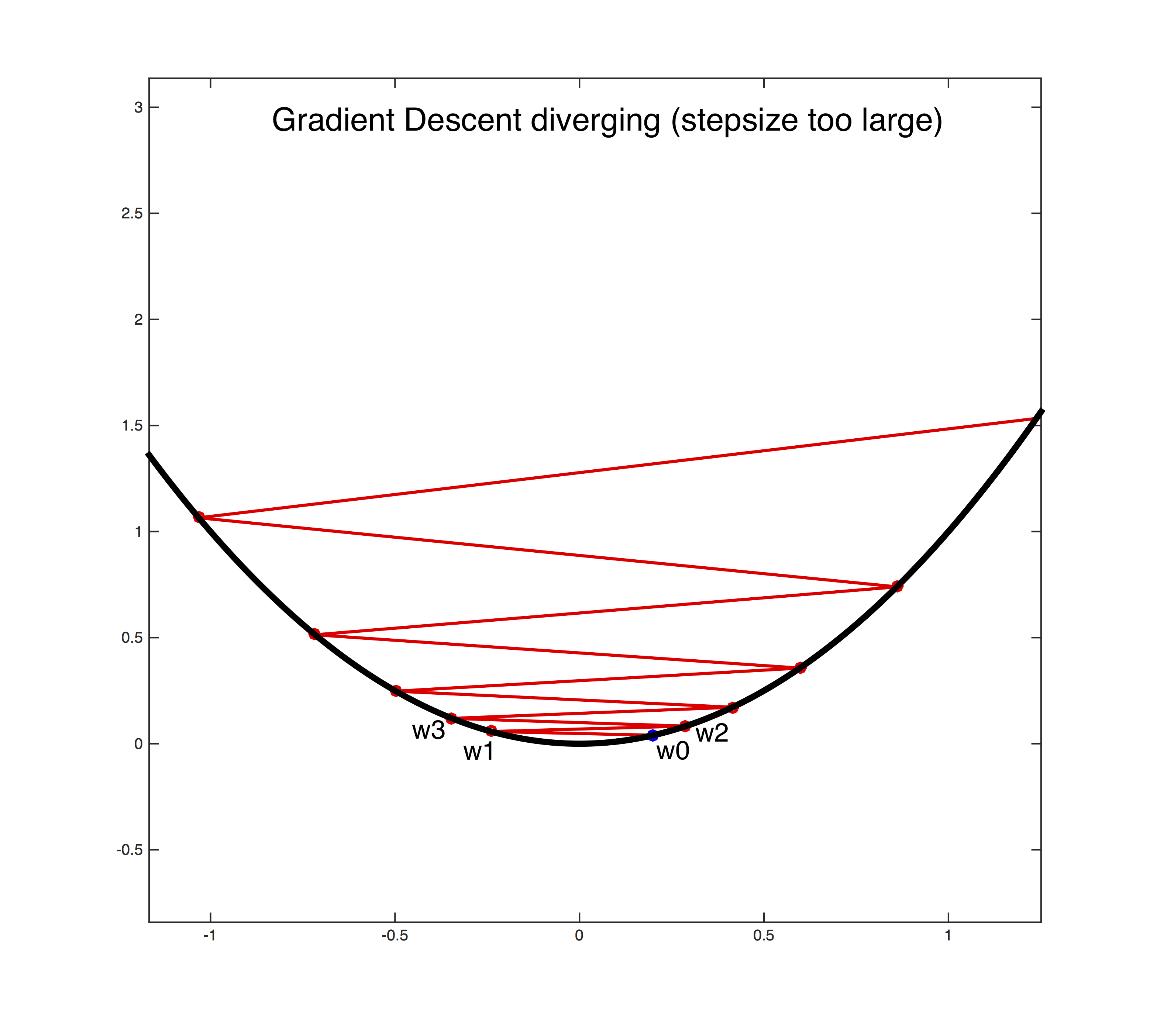

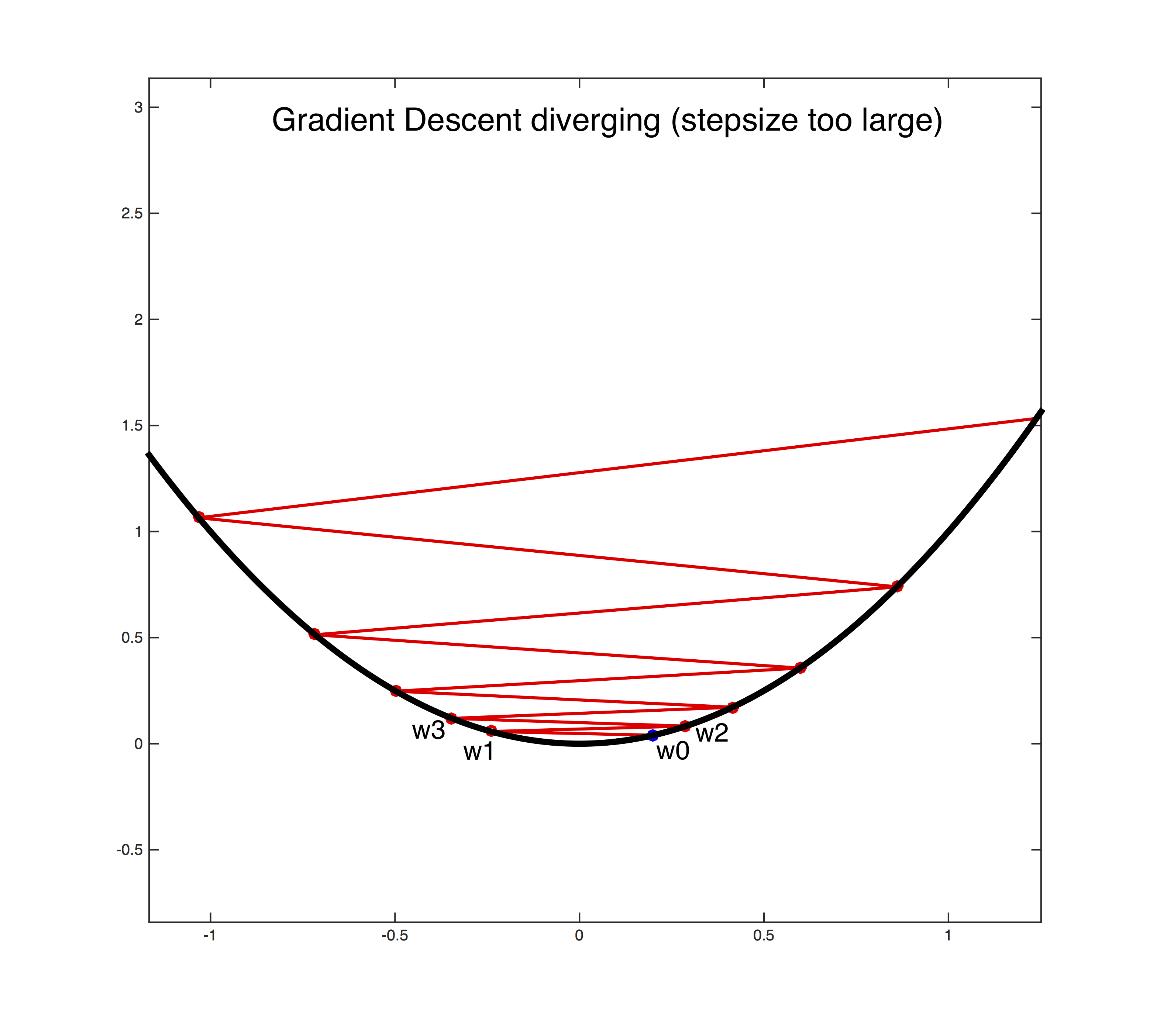

This hill-climbing metaphor for career exploration is similar to the way that a neural network “learns”. The key concept that we need to apply is alpha, or learning rate. Learning rate describes the magnitude of updates that the network makes for each new data point encountered. This affects both how fast the algorithm learns and whether or not we actually reach a minimum.

To make this a bit more concrete, imagine a neural network that attempts to classify images of pieces of food:

- If the learning rate is 0, each new piece of information will not update our classifier at all. The network simply ignores all new data points.

- If the learning rate is 1, each new piece of information will be the only piece of information that the classifier takes into account. We’ve built a this photo of a hot dog vs. everything else classifier, which isn’t very interesting.

- If the learning rate is too low, the model will learn very slowly, though it will eventually be able to distinguish different types of food.

- If the learning rate is too high, the model will learn quickly. However, the model also runs the risk of having a high error rate because it overfits the most recent data. It “bounces” between different understandings of food, heavily influenced the most recent pieces of information it has encountered.

When setting up a machine learning model, people will often “tune” the parameter by trying out a few different learning rates to define the optimal rate for the particular algorithm. But we can’t run simulations of our careers and then choose the optimal learning rate after reviewing the results.

If someone has a career learning rate that is too high, they bounce around. They have tons of ideas for their career, maybe start new businesses, try to grow their skillset, but get partway through and then jump to the next endeavor. Conversely, if their learning rate is too low, they take too long to reach the global maximum. They may spend 30 years climbing a small foothill when the terrain contains the Rockies.

So why don’t people quit their job at large tech companies? They have the wrong learning rate for the neural net of their careers. They’ve become stuck at a local maximum.

Hazing as the Path to Brotherhood

“Whoever fights monsters should see to it that in the process he does not become a monster. And if you gaze long enough into an abyss, the abyss will gaze back into you.”

– Friedrich Nietzsche

A key element missing from this machine learning analogy is that our preferences change over time. Because most people experience loss aversion, setting out on a certain path makes it harder to explore other paths.

This strikes me as the strongest argument against the effective altruism concept of “earning to give”. In Doing Good Better, William MacAskill addresses this directly:

Another important consideration regarding earning to give is the risk of losing your values by working in an environment with people who aren’t as altruistically inclined as you are. For example, David Brooks, writing in The New York Times, makes this objection in response to a story of Jason Trigg, who is earning to give by working in finance:

You might start down this course seeing finance as a convenient means to realize your deepest commitment: fighting malaria. But the brain is a malleable organ. Every time you do an activity, or have a thought, you are changing a piece of yourself into something slightly different than it was before. Every hour you spend with others, you become more like the people around you.

Gradually, you become a different person. If there is a large gap between your daily conduct and your core commitment, you will become more like your daily activities and less attached to your original commitment.

This is an important concern, and if you think that a particular career will destroy your altruistic motivation, then you certainly shouldn’t pursue it. But there are reasons for thinking that this often isn’t too great a problem. First, if you pursue earning to give but find your altruistic motivation is waning, you always have the option of leaving and working for an organization that does good directly. At worst, you’ve built up good work experience. Second, if you involve yourself in the effective altruism community, then you can mitigate this concern: if you have many friends who are pursuing a similar path to you, and you’ve publicly stated your intentions to donate, then you’ll have strong support to ensure that you live up to your aims. Finally, there are many examples of people who have successfully pursued earning to give without losing their values…There is certainly a risk of losing one’s values by earning to give, which you should bear in mind when you’re thinking about your career options, but there are risks of becoming disillusioned whatever you choose to do, and the experience of seeing what effective donations can achieve can be immensely rewarding.

But how many fresh college graduates take a software engineering job at Google while “surrounding themselves with other members of the effective altruism community”? Most people lack MacAskill’s level of circumspection in making career decisions. They stumble into their life decisions rather than making them deliberately. And even for the most deliberate, life is made up more of things that happen to you than things that you control directly.

Once you start down a path, you take on the values of the people that you interact with on that path. My freshman year of college, many of my acquaintances went through a hellish hazing process when when pledging fraternities. In the moment, they said they hated the process. Yet the next year, they were hazing the next class of pledges.

Fraternity hazing prepares people for the bullshit jobs that they encounter after college. These experiences are meaningful precisely because of the wasted effort put into them. The more that we struggle for something, the more we value it.

You see this combination of increased opportunity cost and sunk cost fallacy in all sort of fields that attract ambitious people: finance, law, medicine. Exploration is explicitly discouraged in favor of exploiting the path in front of you. So without a clear plan to counteract these effects, your learning rate declines as you experience some modicum of success.

More broadly, exploration is encouraged for children but discouraged for adults. As a 20- or 25-year-old, it’s exciting to up and move to a new city and start a career in a new industry. Your friends may look askance at you if you do the same at 45.

I’ve experienced this in my own career. As a fresh college graduate, I was in debt, yet turned down a six-figure investment banking job when my startup was funded to the tune of $35,000 by an accelerator in Santiago, Chile. But today, with far more experience, money in the bank, and better business ideas, it’s harder for me to take the leap to be a full-time entrepreneur. My learning rate has declined and I’m less willing to deviate from the hill that I’m climbing.

This is essentially the conclusion that Applied Divinity Studies reaches:

Once you work at Google, you look around, see thousands of genuinely brilliant programmers who aren’t successful, and you get totally trapped. All of a sudden, you go from “I’m incredibly gifted and would do great things if only society wasn’t holding me back” to “there are literally 100 people within eyesight more gifted than me, and they’ve all settled for mediocre jobs, so I guess that’s the most I can hope for”.

Escaping the Matrix

Can anything be done about this? Presumably, this is a net negative for society. People who could be creating value (and employment) by founding companies, pushing the frontiers of scientific knowledge, or casting into being great works of art are instead toiling away at yet another superfluous messaging product for Google.

As explored in the empirical data, many founders start out on the same path that leads to an engineering role at a large tech company. However, they bounce off of this path before their peers begin employment at these companies.

But rather than the selection effect that Applied Divinity Studies addresses – that founders don’t want to work for Google – this may be an example of the exact opposite selection effect. Namely, Google won’t employ the type of people that become founders.

Successful founders are intellectually curious about the world around them, both within and outside of their areas of expertise. They draw connections between seemingly disparate ideas – that is a large part of why they are able to create novel businesses. Steve Jobs bummed around India, experimented with LSD, and sat in on calligraphy classes as a college dropout. Patrick Collison reads about and has questions regarding nearly any topic imaginable. Elon Musk is driving humanity forward in the realms of energy, transportation, space travel, and artificial intelligence, but after graduating from Penn with a degree in physics couldn’t get a job at Netscape.

The best founders are exploring – they have a large alpha. Starting a company requires breadth of knowledge (to make connections) followed by depth into the specifics. In its hiring process, big tech selects only for depth, for those who have optimized for the big tech path.

Smaller, scrappier companies are more likely to tolerate exploration. After the startup that I founded, I applied to the big tech companies and didn’t get interviews. But DoorDash – at the time a 200-ish person company – was willing to take a chance on me.

All of this supports the conclusion that when Googlers do start companies, those companies perform disproportionately well.

So what does all of this mean?

Are we even on the right hill?

In the optimization problem of your career, climbing one hill makes it easier to reach the top of other, higher hills. Working at Google is a great first step to starting a company – you gain legitimacy, meet potential cofounders, can save enough money to not have to worry about personal finances, etc. But paradoxically, frustratingly, the people most likely to make it to the top of this hill are the ones most likely to get stuck there. It’s not that future founders self-select away from big tech. Rather, big tech selects for the people who have optimized for the hill of big tech, not the ones who have explored enough to be successful founders.

Finally, if you work at a big tech company, it makes sense to increase your alpha periodically. Most career decisions are reversible; after your startup fails, you can go back to the Product Manager role at Facebook. But you only have one life. You won’t be able to re-run the simulation with a different learning rate once your career ends.

Notes:

More …

December 12, 2020

I wrote this blog post in 2014, the summer before my senior year of college. I had spent the previous year away from Penn: one semester studying abroad in Argentina, followed by a leave of absence to work at an investment bank in Chicago and then backpack around Australia and New Zealand.

I gained a lot of maturity through this reflective quarter-life crisis. I highly recommend taking time off from school or work in your early 20s if you have the opportunity to do so.

One year ago today, I was in Budapest. In reflecting on how much has changed over the past year, I was reminded of what I wrote about travel back in 2014.

Enter 21-year-old me.

Why Not to Travel

I love to travel. And over the past two years, I’ve been fortunate enough to be able to make travel a priority in my life. Among other trips, I studied abroad in Buenos Aires and traveled around South America, braved a long flight across the Pacific to see Australia and New Zealand, visited friends and family across the country, and participated in a service-learning trip to Rwanda.

Travel has enriched my life. I’ve met people, been exposed to new points of view, and seen things that I would have had no chance of laying eyes on back at home. As St. Augustine said,

“The world is a book and those who do not travel read only one page.”

But the more that I travel, the more I look inward and wonder just how much it has changed me. I wonder if some of the lessons that I’ve learned wouldn’t have been easier and simpler to learn closer to home. I wonder if all of the money I’ve spent on airfare, hostels, and alcohol was worth it. I wonder if my life was changed enough during my travel experiences that I’ll be able to make a bigger impact on the world in the future than I otherwise would have – or if I should have just donated the thousands of dollars I spent on travel to charities that tangibly improve people’s lives right now.

Every time I start a trip, I manage to convince myself that it’s going to be life-changing. That somehow the experience of physically being somewhere different will fundamentally change me – make me more outgoing, more interesting, more motivated to learn new languages, more likely to walk up to that girl in the bar, more like the Dos Equis man.

I think this is in part what has been sold to us today. Travel has become commoditized and romanticized. We’re hooked on images of exotic lands, pristine beaches, new adventures, strange tongues, and moonlight trysts. It’s a mental state, an attitude that companies try to package and sell to us. They claim: “If only your surroundings change, so too will you as a person. You can be anything that you want to be; you can be the person that you’ve always dreamed of being.”

The more that I travel, the more I realize that the whole claim, while alluring, is utter bullshit. I’m the same person in Argentina that I am in New Zealand that I am back home.

We all expect that travel will be “life-changing” or “incredible”, so we only share the highlights of our trips. We don’t tell our friends about the long nights spent sleeping on airport benches, the lost luggage, the feelings of loneliness thousands of miles away from anyone in your support network, the boredom as we lie in bed at an empty hostel in a tiny town in the middle of nowhere with nothing to do at 10 p.m. on a Saturday night.

Our problems don’t disappear when we travel. We still have the same worries, insecurities, anxieties, vices, and character flaws that we do at home. Physical location doesn’t change any of that. Yes, travel can lead to incredible growth experiences, but you have to work at it, just like anything else in life. Changes don’t magically occur.

Emerson recognized this. He claimed,

“Travelling is a fool’s paradise. Our first journeys discover to us the indifference of places. At home I dream that at Naples, at Rome, I can be intoxicated with beauty, and lose my sadness. I pack my trunk, embrace my friends, embark on the sea, and at last wake up in Naples, and there beside me is the stern fact, the sad self, unrelenting, identical, that I fled from. I seek the Vatican, and the palaces. I affect to be intoxicated with sights and suggestions, but I am not intoxicated. My giant goes with me wherever I go.”

I agree with Ryan Holiday that there is no inherent value to travel. You don’t win an award for having more stamps in your passport than your friends. Talking about all of the places that you’ve been comes across a little bit like bragging about your SAT score. Nobody cares and everyone is just a little bit put off.

I’m guilty of this myself. When I’m on a trip, I find myself wondering about what countries I can “do”. As if flying into a country and being there for a day or two somehow makes me a more valuable human being.

All that being said, we can work to make travel incredibly valuable. Travel can be a great learning experience, can enhance and enrich our lives. But we can’t let it fundamentally define our lives.

The first step is to define why you’re taking a trip. Have a purpose or an objective. Do you want to learn about a new language and culture? To escape the normal routine of everyday life? To just lie on the beach and relax?

Any of these are fine. But be honest with yourself about what you’re doing. And be realistic about your expectations for what the trip will bring. Realize that the whole concept of “things falling into place” or “things just happening” is ridiculous. You have to work to make those great experiences happen.

Seneca once said,

“Travel and change of place impart new vigor to the mind.” It’s definitely true that travel can recharge your batteries and give you the perspective that you need to take on new projects back at home.

But he also claimed,

“They [travelers] make one journey after another and change spectacle for spectacle. As Lucretius says ‘Thus each man flees himself.’ But to what end if he does not escape himself? He pursues and dogs himself as his own most tedious companion. And so we must realize that our difficulty is not the fault of the places but of ourselves.”

Travel to enhance your life. Not to escape your life. You can’t outrun your inner demons. Your physical location doesn’t matter so much as your mental state and actions. Wherever you happen to be in the world.

What I’ve Learned from Travel

It’s been said that all travelers are either running from something or looking for something. For most people, it’s probably a combination of both. And while I just said that you can’t romanticize travel as the solution to all of your problems, I still find a lot of value in travel. You just have to be running away from and towards the right things.

Personally, I love the novelty of travel. I’m running from monotony and my day-to-day existence, in which I’m not as mindful as I could be. (I know, I’m working on this…) I’m running towards new experiences, new languages, new cultures, and new people. When I’m on a trip, out doing things, I feel alive, as if I’m an active participant in all that life has to offer.

Travel like this can be invigorating and have positive effects even when we return home. We need periodic breaks from work and everyday life in order to be more productive and happy.

Beyond those benefits, I’ve also learned a lot through various trips. If you do it right, travel is a great way not to let your schooling interfere with your education. With that in mind, I wanted to share the top lessons I’ve learned and ways that I’ve grown through travel.

Patience & Going With the Flow

If you travel, you will learn patience. When you’re in a country where you don’t speak the language and have to deal with a bag mixup, or you’ve been waiting two hours for a bus and don’t know if it will show up, or all of the trains are shut down without an explanation, you start to freak out. Then, after a couple minutes, you realize that it isn’t the end of the world. You can figure this out and your life will go on. It becomes an almost Zen experience.

When you get back home, you won’t complain about having to crash on the floor of your friend’s apartment or a flight being delayed a few hours. You’ve been through worse. I’m a firm believer that in travel, as in life in general, you can choose to either laugh or cry at just about everything. If you choose to laugh, you’ll be a lot happier. Moreover, you’ll have accrued a lot of funny stories that you wouldn’t have had you just stayed at home. Those stories will pay dividends in bars and at family reunions for years to come.

Talking to Strangers & Getting Out of My Shell

The first trip that I took completely alone was a few months ago in New Zealand. The first few days, I was quiet and just read. It was nice and a really good opportunity for me to decompress after working really long hours for the previous three months. But after a while, I started to get bored.

New Zealand – Heaven on Earth

I quickly realized that there were only two options here:

- Stay quiet and remain bored and lonely.

- Start talking to people.

So I bought some beer and shared it with my roommates in a hostel. Surprise – they didn’t bite my head off. Everyone was in the same situation that I was and wanted to meet new people. I got over my fear of going out alone. The reality is, it’s not a big deal to go to a bar, or grab dinner, or do anything by yourself. Nobody really cares – they’re all too worried about themselves.

One of the best things about travel is the people that you meet. You make friends who are completely different from you and learn entirely new world views. People who travel are some of the most open-minded and interesting people that you’ll ever meet. The traveler population self-filters – anyone who is closed-minded or boring will just stay at home.

Additionally, everywhere I’ve been, I’ve found that people are generally proud of the place that they are from. That’s not to say that they’re jingoistic, or have a misconception that where they live is a utopia. Rather, they can see the good in where they live and are eager to share that with other people. As a traveler, it is an incredible experience to be on the receiving end of this energy and to learn firsthand about a culture from someone who is enthusiastic about it.

How to Listen

Travel can teach you how to deal with myriad people and situations. When you’re in a place that you’re not familiar with, you are constantly absorbing information. Every cab driver, waiter in a café, or person that you meet in a hostel has a story that you can learn from. And when you’re in this state of absorbing information, you really learn how to listen.

When you talk to most people, they are (in a best-case scenario) thinking about what they will say next to continue the conversation. Truly listening, focusing 100% of your attention on the person that is talking to you, is an invaluable skill. People notice. Travel causes you to be more present in the moment – it can also cause you to be a more present listener.

You Won’t Get Kidnapped, Murdered, Etc.

The media completely blows out of proportion the risks of traveling abroad. Talking about the great experiences that people have abroad just doesn’t make for good news. But the vast majority of travelers I’ve talked to have never encountered the slightest issue.

Granted, you have to take obvious precautions. Talk to the locals about which neighborhoods to go into and which to avoid. Don’t get too drunk. Don’t travel alone down sketchy alleys at 3 am. Don’t get involved in drug deals with cartels. Don’t visit Syria right now.

But even in places with lots of violence, the violence doesn’t revolve around tourists. People realize that if you start to kidnap or kill tourists, they stop coming to your country, which just hurts business for everyone.

There will be occasional muggings, kidnappings, and even deaths. But this stuff happens in the US, too. Imagine if we were to judge New York City based solely on the 9/11 terrorist attacks, or Chicago based on all of the murders that happen there (over 500 in 2012). That’s exactly what we do with other countries.

Frankly, I felt safer living in Buenos Aires than I do living now in Philadelphia. If you take the necessary (i.e. obvious) precautions, the risk that something will happen to you is minimal.

Spanish

I spoke Spanish pretty well before I left for Argentina, but by the time that I got back I really felt like I was fluent. There is a huge difference between being able to speak the language in a classroom and being able to speak it in everyday life. I found that I was able to understand everything that was said in the classroom, but was challenged in trying to talk to my peers. All of the slang and the stronger accents that people use with one another in casual conversation made it much harder to communicate for me, as I learned the language in a classroom. But by constantly being exposed to that slang and normal, everyday speech, I soaked up the language like a sponge.

Immersion is the best way to learn a language. And in the Internet Age, you can work to get that at home, but there’s always a huge temptation to fall back on your native tongue. Moving to Argentina and being away from my entire English support network forced me to learn Spanish. At first, after concentrating hard to communicate for as few as 15 minutes, I thought that my brain was going to melt. But gradually, it got easier and easier. Being fully surrounded by the language increased my skills more than classes ever could.

Being Selfish is Okay

Travel is principally for our own benefit. That should be recognized. There’s nothing wrong with going to Mexico and hitting the beach. The entire economy of some tropical countries is predicated on tourism. By traveling, you’re doing your part to stimulate the local economy.

However, “voluntourism” has become very popular lately. The idea is that you spend your vacation doing service work – building houses in Nicaragua, or helping with a water project in West Africa. This concept has come under a lot of criticism. Quite frankly, the money that is spent on these trips would be better spent if it were sent to the communities directly. Then, local experts can be hired to work on these projects. This both ensures that the construction is sound (after all, experts, rather than a group of well-meaning but ultimately clueless kids, are working) and the local economy is stimulated.

This was an issue that I wrestled a lot with prior to my trip last summer to Rwanda. With a group of Penn students, I spent 10 days living in a community for high school-aged children who were orphaned during the genocide. I wondered about the impact that we would really make. Would it be better to just donate the money, rather than spend thousands of dollars to travel there?

I came to recognize that I didn’t change the world during this trip. Quite honestly, if my goal were to make the most positive impact right now, I would have donated all of the money to a quality charity that works on infrastructure projects in Rwanda.

I realized that the trip was primarily for myself and my education. That’s fine. I learned firsthand what life is like in Rwanda. And I hope that in the future, as I earn money and gain professional experience, I’m able to give back and make intelligent decisions about giving based on what I experienced in Rwanda. I hope that this trip will allow me to make a greater positive impact in the future than I otherwise would have been able to.

I learned that in general, these trips are primarily for the participants’ benefit, not the benefit of the local community. The positive impact comes from what the participants learn and what actions they take when they return home.

My Travel Limits

As great as travel is, at some point you’re going to want to come home. The time period is different for different people, but eventually the vast majority want to put down roots somewhere. Maybe you’re done with a trip after two days, maybe after two weeks, two months, two years, or even two decades – at some point you want to come home.

I reached my limit during my study abroad in Argentina. I think that at this point in my life, I can travel and be away from friends and family back in the US for about four months. But when I reached that point in my trip, I started to get homesick and was ready to go home.

Conclusion

Ultimately, travel has caused a great deal of introspection and led to a lot of personal growth for me. I truly think that travel, when done right, can be one of the most valuable experiences that life offers.

Getting to distant places is cheaper, faster, and easier to do now than at any other point in history. The world is your playground. Get in the sandbox, get dirty, and see what you can learn.

More …

December 7, 2020

Back when the country locked down in March, like many others I hopped on Zoom calls with family and friends where we speculated about when we’d be going back to work in the office. I didn’t realize it then, but (at least for me) the answer is: Never.

Work From Home’s Dirty Little Secret

Great cities attract ambitious people. If you’re looking to make your mark on the entertainment industry, you move to Los Angeles. If you want to become a financial Master of the Universe, you move to New York.

Historically, the downside to leaving one of these cities has been losing its network effects. This is why digital nomadism never went mainstream – if any smart, ambitious people in this instance of the Prisoner’s dilemma chose to work in-person, it created an equilibrium in which everyone else who was looking to get ahead needed to do the same. COVID creates a new Schelling point in which people can choose to work remotely, precisely because everyone else is also working remotely. They lose fewer of the network effects than they would have a year ago.

So for a substantial minority of white collar workers, COVID has actually improved lives.

COVID catalyzed a burgeoning remote work trend, which is in turn is upending the status quo of our framework for choosing where to live. Previously, the primary consideration for what city to call home was:

- Your current job

- The local labor market for your industry

- Everything else

COVID has removed #1 and #2 (at least in the near term), meaning that people are now choosing where to live based on the ever-nebulous “Everything else” category. Do you prioritize proximity to family? Access to outdoor activities? Want to create a co-living community with a bunch of friends? Now, you don’t have to give up the career opportunities of living in the big city to move to a kibbutz – you can do both. Just make sure that you have a good home office setup wherever you do choose to go.

Both anecdotes and data bear this out. Home prices in lifestyle cities like Austin and Salt Lake City are up, while rents in SF and NYC are down. Airbnb bookings, especially long-term stays (a leading indicator of home sale demand), are through the roof in towns within an hour or two of urban centers.

What does all of this mean? Well, if you’re still paying rent in New York or San Francisco and don’t have a compelling reason to do so: leave now, before prices rise in the cities that young people are now flocking to. You’ll increase your savings by spending your high salary in a low cost-of-living city.

On the other hand, if you’re happy with where you live, now is a great time to get a new job. With the labor market now untethered from your geographic locale, you can enjoy your current lifestyle while locking in the salary of a much higher cost-of-living city. The key is to do this soon – before companies start adjusting salaries for the cost of living where a given employee is located.

The Bear Case 🐻

The advice I just gave assumes an indefinitely long work from home future. However, given a strong Bayesian prior of working in person, what is actually likely to happen?

While we’re working from home, those least affected are people in the later stages of their careers. They have a large amount of social capital and an existing network, meaning the marginal interaction for them in an office is less valuable. So they have the luxury of being able to work from home without adverse consequences.

Conversely, those early on in their career have the most to gain by working in an office. They are eager to establish themselves, and the best way to establish a the track record of work performance and build a large rolodex is through making a positive impression face-to-face. So they lose the most due to an environment of working from home – potentially slower promotions and lower earnings than they would otherwise have. Additionally, once working from an office (at least part of the time) becomes viable, all it takes is a few ambitious people looking for face time to defect to the office to make in-person work the norm once again. So unless everyone is working from home – from the C-suite on down – no one will be.

Back to cubicle hell

So it’s far from certain that the future of work is more than a small minority of people being able to work from home. Byrne Hobart argues that the serendipity of in-person interactions coupled with the network effects of cities create a future in which people can work from home, but also commute to the office for important meetings. Packy McCormick also envisions a hybrid model.

Further, some companies already adjust salaries based on cost of living. This is the reason that my brother, a Google engineer, hasn’t left the Bay Area. He’d be taking a pay cut if he moved anywhere else. In Closing the Remote Work Arbitrage, Byrne Hobart explores the second- and third-order effects on this phenomenon:

VMWare is cutting compensation for remote workers in cheaper parts of the country. An equilibrium where workers all work from home and earn the same wage selects for workers to move to cheap parts of the country, so it’s not stable. But an equilibrium where companies select wages based on where remote workers live is also hard to maintain; it’s hard to measure any productivity difference between someone working in San Jose and the same person working in rural Wyoming. The tech labor market remains liquid, so workers who are underpaid because they work somewhere cheap will get picked off by employers who use a broader remote wage scale.

The most stable setup would be to bucket workers into three categories: 1) can commute to the office once that’s possible, 2) can’t commute, but can take a short direct flight, or 3) would need a full day of travel to get to the office.

What tech companies are talking about instead is localizing wages based on cost of living. This has a very interesting side effect: it’s a de facto subsidy for single employees to move to the most expensive place they possibly can, because their personal expenses are lower (smaller homes, car optional, no school, less healthcare), so their disposable income benefit would be higher. And since dating is a two-sided market, any subsidy that encourages single people to move somewhere will encourage other young single people to follow them. Cost-of-living-based compensation would be very positive for the economic recovery of big cities.

For those of us who enjoy the freedom of working remotely, Moloch strikes again.

Thinking 10 Years Out

This analysis is all done on the social level. What if companies decide that the cost savings of having a remote workforce – no need to pay high rents, lower salaries for cost of living, etc. – outweigh the negatives of the serendipity of in-person interactions? At that point, how much more of a leap is it for them to start recruiting employees outside of the US to further lower costs?

White-collar workers in the U.S. are about to realize what blue-collar workers did 50 years ago. They are in for a rude awakening when they realize that a college degree and the ability to copy and paste in Excel does not give you a competitive advantage in the global labor market – especially when your competition is more than happy to work for half of your salary.

This is the thing that nobody seems to be talking about, the thing that scares me the most about this brave new future of highly-skilled work: we now compete with the entire world.

But we’ve had remote work tools for over a decade now. If this were the case, wouldn’t it have happened already?

Let’s explore what causes companies to draw from a local labor pool:

- Quality control. Companies don’t want to be scammed by people abroad who will take their money and abscond with it, or just produce low-quality work. In-person, at least they can measure if the person they hired is in the office every day.

- Trust. Related to quality control, but it’s draining and unproductive to worry about whether someone can be trusted to actually be a good worker. By having a degree from a reputable and recognizable university, or being within a degree or two of connection in your social network, a potential hire signals that they are more likely to reflect positively on you.

- Culture. You want to work with people that you like to be around and who understand the same references as you. For better or worse, having a shared cultural baseline in the business world is important.

- Communication bandwidth. In-person interactions convey much more than an email can. Communicating asynchronously while working across multiple time zones creates long delays that a 30-minute meeting could solve. The easiest way to ensure high-bandwidth communication is to get people into the same room.

COVID has forced us to revisit these assumptions. How much of this is reality, and how much of it is simply defaulting to what has been a norm for centuries? By forcing us to adapt to a remote work world, COVID has shown us that while these four problems with remote work still exist, they are not insurmountable obstacles. And these obstacles become much more palatable for companies to take on when they can slash their costs by doing so.

I’m already seeing this. The company where I work, TRM Labs, embraced remote work pre-COVID. Pre-pandemic (and today), the entire Machine Learning team is located abroad: the team lead in France and three engineers in Egypt. This is highly skilled, complex work that will only scale up in the future. When I was still at Oscar Health, almost all of our new job listings were listed in Tempe, rather than NYC. Why pay a future employee a New York salary when you can get them for 75% of the cost – especially if they’re going to be working remote anyways?

The internet creates power law distributions. A select few companies will be able to pay above-market rates to attract top talent. Employees of lesser-tier firms, or those without a particularly rare skillset, will realize that their salaries were propped up by a scarcity of local highly-skilled labor. A global power law distribution of this type of labor bodes poorly for them.

Right now, we’re all just along for the ride. We’re in a strange liminal state where the old rules apply and the labor market hasn’t adjusted yet. But in the next few years, there will be an inflection point. And fueled by Zoom, the Silicon Valley caste system will spread.

Notes:

More …

December 2, 2020

This blog has been dormant for the past three months. Apologies to my many doting fans. I was getting into a great posting rhythm towards the end of the summer, but life got in the way. A couple of personal updates:

- My road trip is going well. At the very least, better than these stories. I spent a few weeks driving across the country before settling in Austin for a month.

- I got a new job! I have completed my transformation into the Übermillennial; I now am not only a digital nomad, but also work at a crypto company. I’m an early employee at TRM Labs, a company that prevents fraudulent transactions on the blockchain. This new job incorporates a lot of writing, so I hope that having my livelihood depend on writing output has the positive externality of more creative juices flowing for my personal writing.

Between driving across the country, interviewing for new jobs, and finishing work at Oscar / starting work at TRM in November, I haven’t made as much time as I’d like to write. That will soon be rectified. Upcoming posts to look forward to include:

Giddy up.

More …

September 3, 2020

Over the past few months, as I’ve worked to turn personal notes into public blog posts, I’ve been wrestling with a troubling notion: Do I have any original thoughts?

I’m not sure. I find that a lot of what I think and write is just rehashing what others have said before me.

But the even bigger question is: Does it matter?

What Is an Original Thought?

There are very few true original ideas. By “original ideas” I mean true zero-to-one insights. Not zero-to-one in the way that term is casually thrown around by venture capitalists, but actual insights that change the world. Things like:

- Gutenberg’s printing press

- Shakespeare’s plays

- Kant’s moral philosophy and epistemology

- Einstein’s theory of relativity

- Newton / Leibniz inventing calculus

If this is the bar for an original idea, few human beings will ever have one.

But let’s lower the bar a bit. We can define an “original thought” as an insight about the world that someone hasn’t had before. Even here, the notion that no one else has ever had a similar idea seems to strain credulity. I can’t know for sure (the problem of other minds), but it seems to me that someone at some point in history would have the same thought that I do.

Distilling Others’ Insights

For a long time, I resisted the fact that there is a value in repackaging and disseminating others’ ideas. For years, I’ve watched people like Mark Manson, James Clear, Tim Ferriss, and Ryan Holiday successfully implement the following playbook:

- Take a primary source (often one that has been around for hundreds of years)

- Distill key insights from it and summarizing them on a blog or podcast

- Grow an audience

- Parlay that audience into book deals, speaking engagements, investment opportunities, etc.

While following these authors, I held the contradictory thought that because I already knew something (or could go to the primary source myself) it didn’t make sense to write about it publicly. I was waiting for a new insight to share.

Yet this discounts the fact that just because I know something doesn’t mean that others know it. Many don’t, and they don’t have the time or inclination to dig into primary source material. I’ve found it helpful to think about this through the lens of abstraction layers. Some people want to understand a topic in great detail. Others are just focused on what key insights they can extract to better their lives. Additionally, for concepts to stick, people need to be taught in different ways: with different stories, through different media.

So you don’t need to have some breakthrough insight to share ideas. We’re all just putting our own spin on preexisting information. By writing online about some idea, you:

- Indicate that you’ve given the subject enough thought to understand it better than the majority of people

- Share the story of how to apply that idea to a particular set of circumstances.

Idea Generation vs. Application

We’ve established that:

- There are relatively few true original thoughts/ideas.

- It is likely that someone else has already had the thoughts that I have had.

- There is value in distilling key insights and disseminating them to a wider audience.

Should having original ideas even be our focus? One thing that I’ve learned in the startup world is that ideas are cheap. Everyone has ideas for the next billion dollar company, but it’s the execution – the application of those ideas in a specific context – that matters.

Elon Musk doesn’t have original ideas. He wasn’t a founder of Tesla. SpaceX was not the first private space company. He is an amazing marketer and draws attention to his projects, which attracts the capital and talent that allows his vision to become a reality. He is the epitome of “fake it until you make it”. I don’t mean this as a criticism – I admire Elon Musk and think that he is doing an incredible job of pushing the world forward and shifting the Overton window when it comes to space exploration and clean energy. His execution is what matters.

Further, why do I value original thoughts in the first place? Is it because I value logic and thinking from first principles? Or is it – if I’m brutally honest with myself – because others claim they value logic and originality and I want to be seen as someone who exhibits those traits? René Girard’s mimetic theory scores a point.

At the end of the day, it’s a good problem to have if I’ve managed to cultivate a space where the five people I spend the most metaphorical time with are those whose ideas elevate me. If I’m learning from the best and implementing smart ideas, the genesis of the idea doesn’t matter. Doctors don’t worry that they’re copying other doctors’ best practices. In fact, this is encouraged in the medical profession. Similarly, I can provide value by taking lessons from others, applying them to a specific situation, and writing about that process.

Notes:

More …